Introduction

A Markov Chain is a set of transitions from one state to the next; Such that the transition from the current state to the next depends only on the current state, the previous and future states do not effect the probability of the transition. A transitions independence from future and past sates is called the Markov Property. What we are going to do is explore Markov Chains through a little story and some code.

The Story of Mark

The best way to understand Markov Chains, IMO, is to use a simple example. Lets take an average Joe.. We’ll call him Mark. One week we decide to watch Mark to see what he does and we come up with this:

- Sunday: wake up late, eat breakfast at home, take shower, go to church, eat lunch, watch tv, eat dinner, sleep

- Monday: wake up early, take shower, drink coffee, eat breakfast at home, go to work, eat dinner, watch tv, sleep

- Tuesday: wake up early, drink coffee, take shower, go to work, eat breakfast at work, eat dinner, read, sleep

- Wednesday: wake up early, eat breakfast, drink coffee, go to work, eat dinner, watch tv, sleep

- Thursday: wake up early, take shower, eat breakfast, go to work, drink coffee, go out to dinner, sleep

- Friday: wake up early, eat breakfast, drink coffee, take shower, go to work, go to bar, sleep

- Saturday: wake up late, eat breakfast, mow lawn, take shower, drink beer, go out to dinner, sleep

Now it turns out that Mark isn’t as normal as he seems to be. There is a Creatively Intelligent Association (CIA for short) that wants to kidnap Mark. The catch is they need to make sure that no one suspects that Mark is missing.

To do this the CIA decides to build a robot that will look, smell and act just like Mark. In order to get the Markobot to behave like Mark, the CIA builds a Markov Chain to model Mark’s behavior.

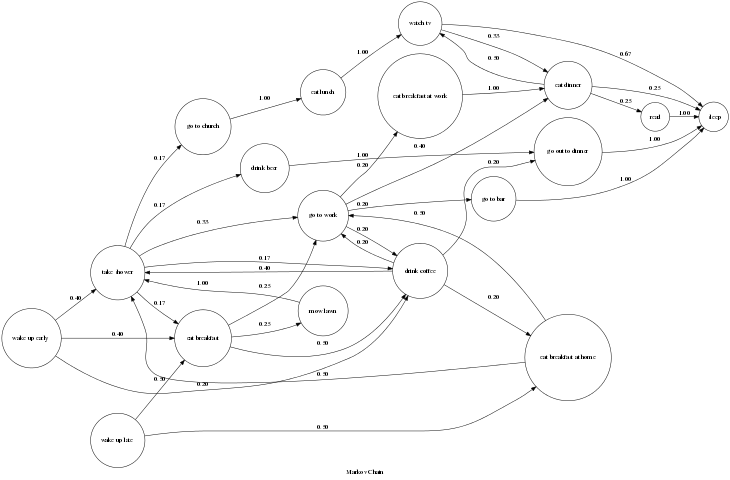

So, After watching Mark for a week the CIA decides it has enough data to build a model of Mark’s behaviour. Applying the data to their Mazing-Markov-Modeler they ended up with this:

The graph’s nodes represent the states that Mark can be in. The edges represent the probability of each transition from one state to the next possible states.

So, back to our story, the CIA uploaded their Mark-Model into their impeccably designed Markobot, kidnapped Mark, and started reading his thoughts after they tapped his eyelids to his forehead with scotch tape.

Oddly enough the Markobot didn’t last that long before it got fired from Mark’s job and his friends started suggesting that he (it?) get some professional help. You see, not long after the Markobot was deployed it started waking up late and going to church on Thursday and showing up at the office with coffee in hand on Saturday.

Obviously this is because the Mark-Model that was put into the Markobot knew nothing about the days of the week. As far as the Markobot was concerned Wednesday was the same as Sunday and the weekend was no different from the rest of the week.

It didn’t take the Creatively Intelligent Association too long to figure this out and soon enough they updated the Markobot with a new Mark-Model that took the day of the week into consideration.

But even so, the were still a lot of odd behaviours that the CIA’s best behaviour modelers couldn’t fix. On some days the Markodroid would wake up, take a shower and drink coffee only to go back and take a shower again. Other times it would go for days without taking a shower.

After years of research and prototyping and burning through billions of tax-payer dollars, the Association figured out that Markov Chains weren’t the best way to model peoples behaviour. This is because what a person does next depends on both his/her past experience and their expectations for the future, not just what they are doing now. In other words the Markov property doesn’t apply to a person’s behaviour.

However there are a number of systems that do exhibit the Markov property and Markov Chains are pretty good at modeling them. Even more interesting, it turns out that Markov Chains can be used to identify “abnormal” behaviour of systems that don’t exhibit the Markov Property. For example if Mark were to wake up and then eat dinner right away out model would detect that as “abnormal” because it has very low (Zero) probability of happening.

Design

I think we’ve talked enough about Markov Chains and it’s time to get down and dirty building them. Our language of choice is going to be Scala. I chose Scala for two reason: First of all I’m learning Scala so this is a chance to get a little practice. The second reason is because Scala’s collections and functional programming style fit the problem we’re trying to solve.

On the abstract level we know that a Markov Chain is a directed graph where the nodes are the different states of the system we’re modeling and the verticies represent the probability of transitioning from one state to the next.

We’re left with figuring out what interface we want to expose for interacting with Markov Chain, and how to implement the graph on the machine level.

When dealing with Markov Chains there are two major things we need to do. The first is to train the Markov Chan with a given set of transitions. The second is to get the set of possible transitions and their probabilities given a state. To do this our implementation is going to expose two functions:

-

addTransition(prevState: Sate, nextState: State)As we are creating a model of the system we are observing, each time we move from one state to the next we add the transition to model we are creating.

-

transitionsFor(state: State)This function will return a list of possible next states along with their probabilities.

As far as the implementation itself goes there are two major schools of tough when it comes to dealing with directed graphs in computer science. The first first is store a nodes data and vertices in the same structure (Think linked-lists or binary trees) which works great when you are dealing with the graph item-by-item or recursively. The second is to store a set independent nodes and than a set of connections between the nodes (the vertices).

For our purposes we are going to associate each state with a set of transitions to possible next states. To do this we are going to create a helper class called MarokvTransitionSet that will store the transitions and probabilities for a single state.

Thanks to MarkovTransitionSet implementing addTransition and transitionsFor becomes trivial.

def addTransition(prevState: S, nextState: S) = {

val transitions =

if (transitionMap.contains(prevState)) transitionMap(prevState);

else new MarkovTransitionSet[S]()

val newTransitions = transitions.addTransition(nextState);

new MarkovChain(transitionMap.updated(prevState, newTransitions));

}

First we check if we had encountered the state before, if we have then get its transition map or else create a new transition map. After that we add the new transition to transition map and associated the updated transition map with the state.

As for getting a state’s transitions and their probabilities we just look up the state’s transition map and dump it.

def transitionsFor(state: S) = {

transitionMap.get(state) match {

case Some(transitionSet) => transitionSet.toList

case None => List[(S, Double)]();

}

}

Transition sets are the heart of our design for Markov chains but they too are trivial to implement. Based our implementation of addTransition and transitionsFor, transition sets have two core functions:

-

addTransition(state: S): Adds a transition to the target state. -

toList(): return a list of possible target states and their probabilities.

addTransition should simply count the number of times we have transitioned to the target state. When we need to calculate the probability of a transition we simply divide the number of times we transitioned to the target state by the total number of transitions. The implementation of addTransition is as trivial as:

def addTransition(state: S) = {

val count = countFor(state);

new MarkovTransitionSet[S](transitionCounter.updated(state, count+1));

}

def countFor(state: S) = {

if(transitionCounter.contains(state)) transitionCounter(state);

else 0

}

toList is also trivial. All that is required it to loop through all the states and calculate the probability for each transition.

def totalCount():Double = {

val counts = transitionCounter.values

counts.foldLeft(0)((a, b) => a+b).toDouble

}

def toList() = {

transitionCounter.toList.map(tup => (tup._1, tup._2.toDouble/totalCount));

}

The complete source code can be found on github.

Displaying the Data

In order to display the data from the chain, we’ll write a simple grapher that will dump the chain’s graph a .dot file that graphviz can understand. I don’t want t dwell on this too much so here is the code:

package com.circuitsofimagination.markovcahin

object MarkovChainGrapher {

def header(title: String):String = {

"""digraph markov_cahin{

rankdir=LR;

label = "%s"

node [shape = circle];

""".format(title);

}

def footer():String = {

"}";

}

def graphvizulize[S](title: String, chain: MarkovChain[S]):String = {

val states = chain.states;

var allTransitions = List[String]();

for(state <- states) {

allTransitions = chain.transitionsFor(state).map(tup => transitionToString(state, tup._2, tup._1)) ++ allTransitions

}

header(title) + allTransitions.foldLeft("")((a, b) => a+b) + footer();

}

def transitionToString[S](initialState: S, probability: Double, nextState: S) = {

"\"%s\" -> \"%s\" [ label = \"%3.2f\" ];\n".format(initialState.toString, nextState.toString, probability);

}

}

Watching Your Packets

Now that we have a Markov Chain, we need to do something with it. Markov Chains are used in almost everything from speech recognition to games. One easy task to do with Markov Chains is to trace packets through the internet to generate a map of where your packets go and how they reach their destination.

Getting a reliable packet trace is trivial using tracerouts with the --tcp option. One thing I noticed was that packet paths were fairly reliable, as in if you run a trace to the same destination more than once the packets tend to take the same path. Because of that I decided to trace the packets to the Alexa to 100 sites and run each trace once. To run the traces I wrote a simple shell script:

#!/bin/sh

for line in `head -n 100 top-1m.csv`

do

host=$(IFS=","; echo $line | awk '{print $2}')

traceroute -n --tcp $host | grep -v "traceroute" | grep -v '*' | awk '{printf $2 " -> "}' | sed -e 's/-> $/\n/'

done

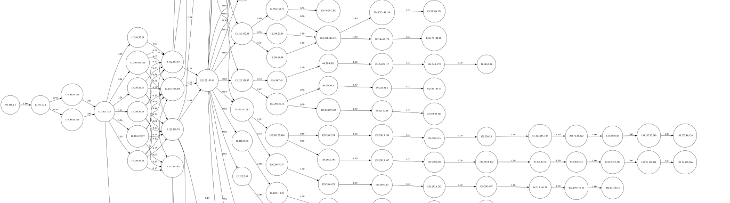

After getting the packet trace data and formatting through our Markov chain you get large image describing the packet traces. Here is a section of the image

The full map is available here